Sutton House

A courtier’s country home in Hackney

Sutton House, Homerton

Ralph Sadleir (or Sadler) was born in 1507, probably in Hackney. The statesman Thomas Cromwell played a significant role in “bringing up and advancing” the young Sadleir, who from early adulthood served as Cromwell’s secretary. Sadleir rose to become an influential courtier and diplomat, a knight and privy counsellor – and one of the richest commoners in the kingdom.

In recent years he has gained a little fame as a character in Hilary Mantel’s historical novels Wolf Hall (2009) and Bring Up the Bodies (2012) and their TV adapation (in which he becomes Rafe Sadler). Mantel visited Sutton House as part of her research for the books.

The house was built for Sadleir in 1535, when it was simply known as ‘the bryk place’. At that time houses of its size were usually constructed from timber beams interfilled with wattle and daub panels. Only grand mansions were routinely built of brick.

Within a decade Sadleir had built himself one of those grand mansions – at Standon in Hertfordshire – and he sold ‘the bryk place’ in 1550.

Much later, the place became known as Sutton House, from the misapprehension that it had been the home of Thomas Sutton (1532–1611), who had in fact lived – and died – in a neighbouring property, which was pulled down in the early 19th century to make way for a (very tasteful) row of houses on the cul-de-sac called Sutton Place.

Large(ish) old buildings on what were then London’s country fringes were typically occupied by a series of moderately wealthy leaseholders (such as merchants’ families) and minor institutions like schools, and Sutton House was no exception. In 1751 it was divided into two houses, both of which were bought by the rector of Hackney in 1891. He converted the reunited Sutton House into the St John at Hackney church institute, a social and recreational centre for young men.

In 1904 a programme of renovation and adaptation left Sutton House looking broadly the way it does today. The ‘barn’ at the back was built as an events space and meeting room, leaving the courtyard enclosed on all sides.

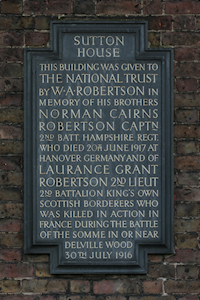

The National Trust acquired Sutton House in 1938 with the proceeds of a legacy from William Alexander Robertson, who had died the previous year. As a plaque on the front wall explains, Robertson made the bequest in memory of his brothers, who had been killed in action during the First World War.

Because this is Hackney not Hampstead, the trust was doubtful about the viability of restoring Sutton House as a historic attraction. Instead the house was let to a varied succession of occupants, including Hackney council’s social services department and the ASTMS trade union in the 1970s, after which the building fell into a dismal state of disrepair.

The trust tried – and failed – to find an appropriate tenant to replace the ASTMS and was on the verge of accepting a property developer’s offer to convert Sutton House into flats when campaigners persuaded it to reconsider. A full-scale restoration was undertaken from 1990 and the house was opened to the public in 1994.

In every respect, the National Trust has (in the end) done its usual fine job here, getting the details right and making the most of a house that has been much messed about with over the centuries.

The information panels are especially good – even explaining why a bit of brickwork is looking mouldy, and what’s being done about it.

The most important and best preserved rooms are presented as they might have looked in Ralph Sadleir’s day, or soon after. The remaining spaces re-create other phases in the building’s history: a Georgian parlour, a Victorian study and so on.

When Hidden London last visited, the exhibition room in the attic had been transformed into a squatter’s bedroom to mark the 30th anniversary of the period in the mid-1980s when the vacant property was illegally occupied – and protected from the worst excesses of theft and vandalism.

The garden area south-west of the house has been turned into the Breaker’s Yard, “playfully celebrating the industrial history of the site.”

As was always feared, Sutton House doesn’t get a huge number of historically-minded visitors, so the National Trust encourages its supplementary use as a community venue, laying on a variety of events and learning experiences for local adults and children.