Wallace Collection

Old masters, armour and a riot of rococo

The Wallace Collection, Manchester Square, Marylebone

Edward Seymour was Lord Protector of England in the late 1540s. His descendant Francis Seymour-Conway was created 1st Marquess of Hertford in 1793, the year before he died. In 1797 the 2nd Marquess acquired the leasehold of Manchester House, which the 4th Duke of Manchester had built a few years earlier – apparently because there was good duck shooting to be had nearby. The 2nd Marquess used Hertford House (as it was soon renamed) as his principal London residence, hosting many lavish parties here.

The 2nd Marquess was not a connoisseur of the decorative arts, but his son, grandson and great-grandson (respectively a refined rake, a neurotic but witty semi-recluse, and an illegitimate philanthropist) were all voracious collectors of furniture, paintings, sculpture, porcelain and other sumptuous items like gold boxes, Venetian glassware and gilded clocks and barometers.

The dynasty’s most prolific (one might even say obsessive) collector was the 4th Marquess, Richard Seymour-Conway. Born in London, he was brought up by his mother in Paris, where he later purchased a central apartment and the Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne.

The 4th Marquess devoted the last 30 years of his increasingly reclusive life to filling his homes with works of art, including furniture by the greatest French cabinet-makers, tapestries, a collection of Oriental arms and armour, and hundreds of paintings – mainly French and Dutch works of the 18th and 19th centuries but some Old Masters too. He never married. When he died at Bagatelle in 1870 he left most of his possessions to his hitherto unacknowledged illegitimate son Richard Wallace, who soon also bought the lease of Hertford House from the 5th Marquess of Hertford (a second cousin of the 4th Marquess).

In 1871 Wallace purchased two collections of European arms and armour; married his long-term mistress, Julie Castelnau, who is said to have been an assistant in a perfumer’s shop when they met; and was made a baronet in recognition of his charitable works and gifts to humanitarian causes. The insurrection known as the Paris Commune prompted him to move back to London, bringing a substantial proportion of his Parisian collection with him. He redeveloped Hertford House, creating a range of galleries on the first floor.

While Hertford House was being converted to accommodate the collection, much of it was exhibited at the Bethnal Green museum, where it was a popular sensation.

When he died in 1890, Sir Richard Wallace left all his property to his wife, who led a secluded existence at Hertford House until her own death seven years later. Lady Wallace bequeathed the collection at Hertford House to the nation – probably in fulfilment of her late husband’s wishes – but she left the house itself to her secretary and adviser, John Murray Scott. He sold the lease to the government and the house was converted into a museum by the Office of Works. The Wallace Collection first opened to the public on 22 June 1900.

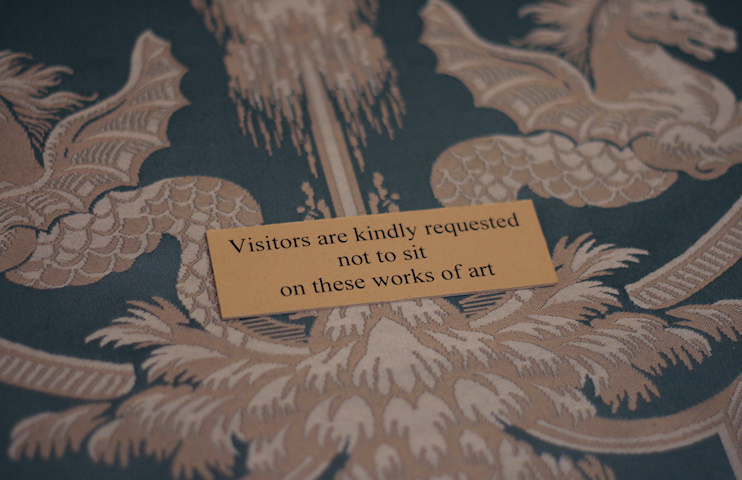

By the terms of Lady Wallace’s bequest, the house’s contents comprise a ‘closed collection’, meaning that nothing may be added to it or taken away from it. However, the trustees have progressively enhanced the presentation of the Wallace Collection over the decades. In particular, a project in the last few years of the 20th century created a lecture theatre, an education studio and new exhibition galleries in the old basement, and a (pricey) restaurant in the covered courtyard. Many other rooms have been refurbished since then.

Also, it was announced in September 2019 that lawyers and art experts had re-examined the terms of Lady Wallace’s will and decided they did not prevent loans, a conclusion endorsed by the UK government and the Charity Commission. The Wallace Collection’s director, Xavier Bray, was quoted as saying: “For me it is a bit like the Hobbit and you see that dragon just sitting on the treasure, not letting anybody get close to it. This is a major new chapter for the Wallace, it’s likely to be transformative in terms of how we work and how our curators and conservation staff think about the collection.”

Hertford House’s highlights include works by Titian, Rembrandt, Rubens, Hals (The Laughing Cavalier) and Velázquez, as well as Louis XV’s rococo commode, some remarkable suits of armour (for horses as well as men) and the finest museum collection of Sèvres porcelain in the world. As the photographs suggest, the Wallace Collection is almost too gorgeous – a bit rich for some tastes – but if you’re fond of the finer things in life and art then you’re in for an exquisite treat.