Florence Nightingale Museum

Florence and other nurses (and their pets)

Florence Nightingale Museum, St Thomas’ Hospital, Lambeth

The founder of modern nursing, Florence Nightingale was born into an upper-class British family on 12 May 1820 and named after the city of her birth. Nightingale was partly self-taught but also trained at the Kaiserswerther Diakonie near Düsseldorf. In 1853 she took up her first professional position – as superintendent of a gentlewomen’s nursing home at 90 Harley Street, where a stone plaque now avers that “Florence Nightingale left her hospital on this site for the Crimea, October 21st 1854.”

In fact, she went first to a temporary military hospital at Scutari (now Üsküdar, a municipality of Istanbul), with a team of volunteer nurses. Here she began her pioneering efforts, especially in improving standards of sanitation and nutrition, thus reducing avoidable deaths. The Crimean campaign has been called “the first modern mass media war” and coverage in the British press made Florence Nightingale a national heroine – and helped her raise the funds and gain influential support to augment her work, both during the war and afterwards.

Following her return to London, Nightingale wrote a seminal book entitled Notes on Nursing and in 1860 established a nursing school at St Thomas’ Hospital, which was at that time located in the Borough, in Southwark.

St Thomas’ Hospital has been based in Lambeth since 1871, and a sub-ground-floor corner of an annexe called Gassiot House is home to the Florence Nightingale Museum.

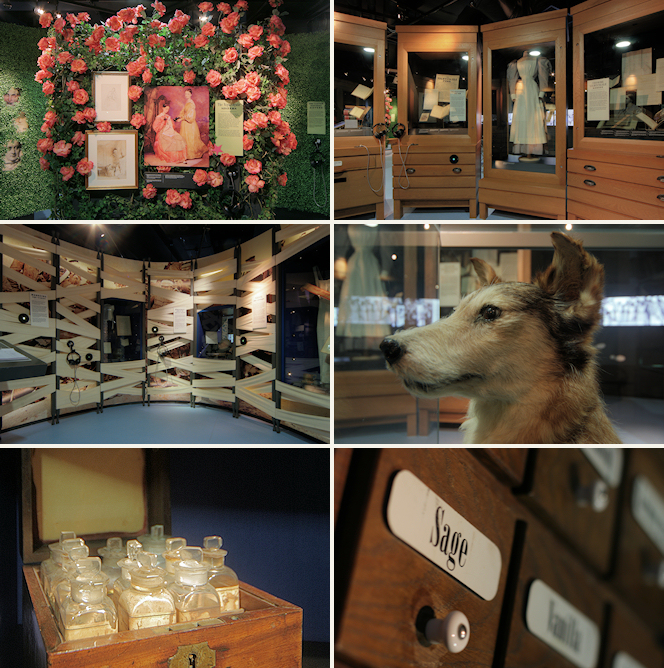

Although the collection here may not be as expansive as one might like – in part because Nightingale shunned the trappings of celebrity – it’s extremely stylishly arranged, thanks to a half-million pound grant from the Wellcome Trust’s Capital Awards scheme in 2010. The museum is basically one big room that has been divided into three ‘pods’, each devoted to a phase of Florence Nightingale’s life, work and legacy – before, during and after the Crimean War.

In addition to all the matters of life and death on display, there’s a handful of more frivolous items, including Florence’s pet owl, stuffed and perched on a branch. Not unlike the Elgin marbles, the little owl (Athene noctua) had been rescued from Athens and brought to England for safekeeping, whence it never returned. Florence’s sister Parthenope handwrote and illustrated a short book on the subject, entitled The Life and Death of Athena, an Owlet from the Parthenon.

A small space (with a thought-provoking video) is devoted to Mary Seacole, the Jamaican-born nurse/herbalist/hotelier/caterer who spent two years in the Crimea – though she did not work with Florence Nightingale, who seems to have disapproved of her willingness to dispense alcoholic beverages to soldiers. Mary Seacole died in Paddington in 1881. She is commemorated by a statue in St Thomas’ Hospital’s garden, erected in 2016.

The museum also honours the work of Edith Cavell, the Red Cross nurse who was shot by a German firing squad in 1915 on the orders of the Governor General of Brussels. Cavell’s pet dog Jack was embalmed and mounted after his death in 1923 and is on loan here from the Imperial War Museum. Jack is shown centre-right in the group of images below.

Like many of London’s smaller museums, there’s a strong emphasis here on educational features, aimed mainly at youngsters – and there’s a profusion of peepholes, through which to view various photographs and film clips. School groups are often in attendance (and the sessions are booked up months in advance) so beware if you’re allergic to kids. Before being set various observational and participative tasks, primary school children get an inspiring talk from an actress playing ‘Miss Nightingale’. I overheard such a performance when I visited for Hidden London, and was very impressed. There’s a more grown-up programme of educational activities for secondary school children.