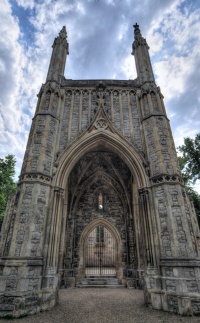

Nunhead Cemetery

Gothic splendour meets untamed nature

Nunhead Cemetery, Linden Grove, SE15

By the early 19th century the unceasing growth of London’s population had led to overcrowding in its church graveyards. Not only did this make burials increasingly undignified affairs but many people believed some sort of noxious vapour or ‘miasma’ rose into the air from the decomposed corpses, spreading diseases.

In 1832 Parliament passed the first in a series of laws that permitted burial grounds to be established on a commercial basis. Newly formed companies seized the opportunity to create spacious, verdant and ‘hygienic’ cemeteries at what were then semi-rural locations on the edge of the city.

The Metropolitan Interments Act of 1850 and its successor the Burial Act authorised municipal authorities to open their own London cemeteries but for two decades profit-making businesses had the market in non-churchyard burials to themselves. The earliest and grandest of their creations were memorably dubbed the Magnificent Seven in Hugh Meller’s London Cemeteries: An Illustrated Guide and Gazetteer, a definitive work now in its fifth edition.

Forming a ring around what is now inner London, the Magnificent Seven are: Kensal Green, Highgate, Abney Park, Tower Hamlets, Nunhead, West Norwood and Brompton. Nunhead is among the largest but least visited of the sepulchral septet. Its expansive lawns and sweeping, tree-lined avenues were laid out in 1840 by the London Cemetery Company, which a year earlier had created the Cemetery of St James, Highgate. The company’s two properties were conceived as a pair, located on hillsides facing each other across London, with St Paul’s Cathedral midway between them.

Nunhead can’t match the roll call of famous names on Highgate’s tombstones but those who know south London’s history may recall the philanthropic gas magnate George Livesey and the bus tycoon Thomas Tilling. A granite obelisk commemorates Scottish parliamentary reformers who were charged with sedition and transported to Australia. The weeping angels and lions’ heads of other imposing memorials mostly honour wealthy individuals who have left no lasting mark on the world.

The cemetery contains 580 Commonwealth burials of the First World War, some marked with individual headstones and the remainder commemorated by name on a screen wall.

Despite occasional initiatives such as the construction of a new south entrance, Nunhead declined in prestige and profitability over the course of the 20th century. During the Second World War its iron railings were removed and the Dissenters’ chapel suffered irreparable bomb damage and was later demolished. Facing bankruptcy in 1960, the London Cemetery Company was absorbed into the larger United Cemetery Company, which finally gave up on Nunhead nine years later. With its gates locked but railings gone, the cemetery succumbed to the inexorable power of nature and the destructive effects of vandalism and theft. The Anglican chapel was set on fire and the catacombs were raided for lead and jewellery.

In 1975 a special act of Parliament enabled Southwark council to buy the site for one pound. With the assistance of lottery funding in the late 1990s, the Friends of Nunhead Cemetery (FONC) renovated the ruined chapel, restored the gates, walls and railings, repaired 50 memorials, laid new paths and cleared much of the overgrown landscape – though extensive swathes of wilderness remain, like the one in the photograph below. The cemetery reopened to the public in 2001. The whole 50-acre site is now a conservation area and grade II* historic park, and part is a nature reserve with a diverse variety of flora and fauna.

The FONC organises regular conservation work for volunteers and conducts a guided tour of the cemetery on the last Sunday of each month, starting from the Linden Grove gates at 2.15pm.