London phrase and fable

London Phrase & Fable

A small selection from Brewer’s Dictionary of London Phrase & Fable (excluding images), published in paperback in 2010

Presented for your browsing pleasure, this particular miscellany focuses (entirely randomly) on music, sport, statues, proverbs and quotations.

Addicks

The nickname of Charlton Athletic FC. The word almost certainly dates from the earliest years of the club’s existence when local fishmonger, and later club vice-president, Arthur Bryan used to provide post-victory suppers of haddock and chips for the players. Allegedly, Bryan would serve the less popular cod in the event of a defeat. The team was soon dubbed ‘the Haddocks’, which subsequently became corrupted to ‘the Addicks’. The club has preferred ‘Robins’ and ‘Valiants’ at times in the past but now officially endorses the fishy sobriquet.

The Arsenal Stadium Mystery

A 1939 detective film directed by Thorold Dickinson (1903–84), in which an opposition player dies by poisoning during a match at Highbury stadium and Scotland Yard is called in to investigate. Several Arsenal players of the time appeared in the film, which was one of the earliest to exploit the British love of football, and one of the very few such productions to have been critically acclaimed, despite its low budget.

as sure as the devil is in London

A provincial saying casting aspersions on the virtue of Londoners. The proverb also crossed the Atlantic.

as the bell clinks, so the fool thinks or as the fool thinks, so the bell clinks

A foolish person believes what he desires. The tale says that when Dick Whittington ran away from his master, and had got as far as Highgate Hill, he was hungry, tired and wished to return. The bells of St Mary-le-Bow began to ring, and Whittington fancied they said: ‘Turn again, Whittington, lord mayor of London.’ The bells clinked in response to the boy’s thoughts.

bacon-and-egg tie

A nickname for the assertive red-and-yellow-striped tie worn by members of the Marylebone Cricket Club.

Billy Williams’ Cabbage Patch

The English Rugby Football Union’s ground at Twickenham, the headquarters of the game, also known as Twickers. It is popularly so called after William (Billy) Williams (1860–1951), who discovered the site and who persisted until it was acquired for rugby in 1907. The latter part of the name refers to the ground’s former use as a market garden. The first match played there, on 2 October 1909, was between Harlequins and Richmond, and the first international was England v. Wales the following year. The nearby Railway Tavern changed its name to the Cabbage Patch in 1959 when England and Wales played Scotland and Ireland in a centenary match. The ground is now also the site of the World Rugby Museum, and tours of the stadium are held six days a week, except when a match or event is taking place.

Boudicca

The British warrior queen, wife of Prasutagus, king of the Iceni, a people inhabiting what is now Norfolk and Suffolk. On her husband’s death (AD 60) the Romans seized the territory of the Iceni. The widow was scourged for her opposition and her two daughters raped. Boudicca raised a revolt of the Iceni and Trinovantes and burned Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium and Verulamium (St Albans). According to most sources, when finally routed by the Roman governor Suetonius Paulinus, she took poison. As ‘Boadicea’, she is the subject of poems by William Cowper and Tennyson. One legend has it that she is buried beneath a platform at King’s Cross station. A tumulus near Parliament Hill was also said to be her burial place, but when it was excavated in 1894 little was found except signs that it had already been dug out before. It is said that, if confirmation had been found, Thomas Thornycroft’s statue of the queen in her chariot would have been erected at that spot, instead of its present site at Westminster Bridge.

Burlington Bertie

A would-be elegant ‘man about town’ or ‘masher’, personified by Vesta Tilley in a popular song of this name by Harry B. Norris (1900). William Hargreaves wrote a well-known parody version for his wife, the male impersonator Ella Shields.

Celery

A laconic bawdy ditty chanted by some supporters of Chelsea FC. Its popularity led a small minority to begin throwing sticks of celery onto the pitch during games; the club clamped down hard on the practice.

A reader adds: The chant first started at Gillingham, season of 1995–6, because celery’s low calorific value is well-known, and at that time they had the heaviest goalkeeper in the league, a man by the name of Jim Stannard. The joke, however, was on the fans: Stannard let in just 20 goals all season, kept 29 clean sheets, and the club won promotion. [Thanks to James McLaren]

Craven Cottage

Originally a cottage orné built in 1780 on the west side of the Fulham peninsula as a country retreat for for William Craven, 6th Baron Craven (1738–91). The cottage burned down in 1888 and Fulham FC established a permanent home on its site in 1896, 17 years after the club’s foundation. In recent times plans for the club to radically rebuild the stadium, or possibly to move elsewhere, have come to nothing and Craven Cottage is likely to remain in roughly its present form for the foreseeable future.

From 1980 until 1984 Craven Cottage was also home to Fulham Rugby League Club. Fulham RLFC played at other London stadia from 1984, eventually mutating into Harlequins Rugby League.

Day

A once-controversial sculpture (1929) by Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) on the exterior of 55 Broadway. The building is graced by ten reliefs, none of which was much appreciated at the time of its construction, including Epstein’s companion piece to Day, Night, and works by Eric Gill and Henry Moore. However, public and press opprobrium centred on Day for its portrayal of a father and his naked son and, in particular, for the proportions of the boy’s phallus. Frank Pick, ‘the man who built London Transport’ and commissioned the work, stood by Epstein and threatened to resign rather than remove the sculpture but Epstein deflected the criticism by ascending the building one night and reducing the length of the offending appendage by 1½ inches (3.8 cm).

don’t be a sinner, be a winner

The mantra of Philip Howard (b.1954), sometimes known as ‘megaphone man’, who around 1994 began haranguing West End shoppers with anti-consumerist, pro-faith messages. In 2006 he was served with an anti-social behaviour order, banning him from amplified preaching in the vicinity of Oxford Circus. He subsequently made appearances elsewhere and sometimes quietly distributed tracts at his old locus standi.

Eagles

The present-day nickname of Crystal Palace FC, promulgated in the mid-1970s following the introduction of a new crest that relegated the formerly dominant image of the glass exhibition hall to secondary, stylized status and added a red and white football surmounted by a blue eagle – later redrawn to look more eagle-like. The redesign was said to have been influenced by the emblem of the Portuguese club Benfica, which is also nicknamed the Eagles (as águias) and uses the bird as a symbol of ‘independence, authority and nobility’. Crystal Palace had formerly been known as the Glaziers.

elementary, my dear Watson

The most famous words that Sherlock Holmes never uttered in the stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. He came closest in ‘The Adventure of the Crooked Man’ (1893).

Although it has not been confirmed, the precise phrase is said to have been spoken on the stage by William Gillette (1853–1937), in one of his famous portrayals of the Baker Street sleuth, and this may have prompted P.G. Wodehouse to put the words into the mouth of his character Psmith in Psmith Journalist (1915). The first documented use of the phrase by Holmes himself came in the closing scene of the film The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1929).

Fever Pitch

A popular sociological study (1992) by Nick Hornby (b.1957), subtitled ‘A Story of Football and Obsession’. It charts the author’s personal relationship with the game as a fan (from the age of 10) of Arsenal FC. The title has obvious punning connotations. A film version (1996), directed by David Evans and starring Colin Firth, presented the original as a romantic comedy. An Americanized version (2005) concerned actor Ben Fallon’s character’s obsession with the Boston Red Sox.

a fool will not part with his bauble for the Tower of London

An ancient proverb, coined before 1500, when the Tower was the storehouse of the nation’s wealth.

frighten the horses, to

To alarm people. The words are attributed to Mrs Patrick Campbell (1865–1940) in Daphne Fielding’s The Duchess of Jermyn Street (1964): ‘It doesn’t matter what you do in the bedroom as long as you don’t do it in the street and frighten the horses.’

get your trousers on, you’re nicked

A line written by Ian Kennedy Martin (b.1936) and delivered by John Thaw (1942–2002), playing Detective Inspector Jack Regan, in ‘Regan’, an ITV Armchair Cinema episode broadcast in 1974. The choice of words epitomized the production’s supposedly realistic portrayal of a rough, tough London policeman who contrasted sharply with the benign characters that had formerly populated most TV crime dramas. The show’s broadly favourable reception led to the creation of a spin-off series: The Sweeney.

Harrow drive

A cricket term that seems originally, in the mid-19th century, to have been applied to an off-drive, presumably thought of as a specialism of Harrovian batsmen. Well before the close of the century, however, those inclined to poke fun at the school’s pretensions were using it to denote a botched or edged drive, and by the middle of the 20th century it was firmly attached to a stroke that sends the ball accidentally off the inside edge of the bat past the leg stump.

Hokey-cokey

A light-hearted cockney dance, popular during the 1940s, with a song and tune of this name to go with it. It was also known as the ‘Cokey-Cokey’, especially in the version written by Jimmy Kennedy in 1945 and recorded by Billy Cotton and his Band, among others.

I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles

The club song of West Ham United FC and probably the most famous English team anthem after Liverpool’s ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’. The song was a music hall favourite in the 1920s, a time when Pears soap was advertised using John Millais’s ‘Bubbles’ painting (1886). Billy Murray, a youth who played for a local school team and tried out for West Ham, bore a remarkable resemblance to the boy in the painting and his headmaster accordingly encouraged supporters to sing ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’ at school matches. The headmaster was a friend of West Ham trainer (and later manager) Charlie Paynter, who introduced the song to his club’s fans. The lyric’s pessimistic tone marks it out from most football anthems.

Itchycoo Park

A song by the east London group the Small Faces that reached No.3 in the British singles chart in 1967. The inspirational park has not been conclusively identified, largely because of conflicting remarks later made by the band’s members. Little Ilford Park is named most often by geo-musicologists but others have proposed Valentines Park, West Ham Park and Wanstead Flats. The ‘itchycoo’ nickname could have derived from the presence of biting insects or stinging flora. Alternatively, the song may have been about Oxford – the lyric mentions ‘dreaming spires’ – or entirely drug-induced, with no connection to any real park, in east London or beyond.

it’s the poor what gets the blame

A traditional cockney expression of lamentation, taken from a music hall song that dates from the late 19th or early 20th century. The song’s title is rendered either as ‘It’s the Same the Whole World Over’ or ‘She Was Poor but She Was Honest’. A 1930 version by Bob Weston and Bert Lee was regularly performed by the comic entertainer Billy Bennett (1887–1942). The lyric exists in varying forms, and has been lewdly adapted for drinking songs, but the gist is always of a country girl who is seduced and abandoned by a wicked squire. Fleeing to London, she receives similar treatment from gentlemen in positions of authority. Finally she throws herself from a bridge into the Thames at midnight. In one version she drowns but in others she is rescued.

Jack Jones

To be on one’s Jack Jones is to be alone; on one’s own. This imperfect piece of cockney rhyming slang appears to derive from the music hall song ‘’E Dunno Where ’E Are’ (early 1890s), written by Fred Eplett and made famous by Gus Elen. The lyric concerns one Jack Jones, a former Covent Garden market porter who has come into some money and now considers himself above his old workmates. He reads the Telegraph instead of the Star, calls his mother ‘ma’ instead of ‘muvver’ and stands alone at the bar drinking Scotch and soda. However, modern usage of the term rarely implies aloofness on the part of the person alone; more often it is close to the opposite – he or she may feel abandoned. For example, ‘You lot went off and left me on me Jack Jones!’

justice is open to all; like the Ritz hotel

The more money you have, the better access you have to the legal system. This oft-quoted remark, or words to the same effect, has been attributed to Lord Birkett, Mr Justice Mathew, Lord Bowen and others.

London Bridge was made for wise men to go over and fools to go under

A saying dating from before the removal of the medieval London Bridge in 1832. Navigation through the arches of the old bridge was notoriously dangerous because of the swirling currents.

a London jury hangs half and saves half

A very old saying implying that busy Londoners had no time to carefully weigh up the arguments in a trial but simply consigned every other defendant to the gallows. It was also said of Essex and Middlesex juries. The city’s historians have been at pains to deny this, stressing that London jurors have almost always inclined ‘to the merciful side in saving life, when they can find any cause or colour for the same’, as Thomas Fuller put it, in his History of the Worthies of England (1662).

Naked Lady

The colloquial name of La Délivrance, a bronze statue of a naked women holding a sword aloft, located at Henly’s Corner, on the North Circular Road. The work of the French sculptor Emile Guillaume (1867–1942), it was inspired by the allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne, which delivered Paris from the threat of German seizure in 1914. The statue was exhibited at the 1920 Paris Salon, where it was bought by the newspaper magnate Lord Rothermere, who donated it to Finchley council in honour of his mother, a resident of Totteridge. Lloyd George unveiled the statue in October 1927 before a crowd of 8,000.

no one likes us, we don’t care

The unofficial motto of Millwall FC, much chanted by the club’s fans to the approximate tune of ‘Sailing’ (Gavin Sutherland, 1972). Also the title of a book by Garry Robson, subtitled ‘The Myth and Reality of Millwall Fandom’ (2000). For much of the late 20th century, sections of the media portrayed Millwall supporters as football’s worst hooligans, sometimes labelling them as white, working-class racists. The chant reflects the fans’ attitude to being thus stigmatized.

North Weezy

An urban slang term for north-west London, especially the NW2 (Cricklewood), NW6 (Kilburn) and NW10 (Willesden) postal districts but even heard in the heights of Hampstead. It is apparently a contraction of ‘north-west easy’. Variant spellings range from ‘North Wheezy’ to ‘Norf Weezie’.

Trawlerman is the most southerly chippie in North Weezy

to do chips with onion gravy.

Ashna Sarkar: ‘Heartbeat’, The Salt Book of Younger Poets (2011)

not a lot of people know that

A catchphrase personifying the actor Sir Michael Caine (b. Maurice Micklewhite, 1933). It originated in a remark made by Peter Sellers to Michael Parkinson in 1972.

Caine was born in Rotherhithe, the son of a Billingsgate market porter, and grew up in Camberwell (where he attended Wilson’s grammar school) and the Elephant and Castle. He has played major parts in more than a hundred films, including Alfie (1966), Get Carter (1971), Mona Lisa (1986), Little Voice (1998) and Harry Brown (2009).

not bloody likely

A line famously uttered by Eliza Doolittle in Act 3 of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1913): ‘Walk! Not bloody likely. I am going in a taxi.’ It caused considerable outrage at the time and the mock-euphemistic ‘not Pygmalion likely’ was afterwards used in literate circles. Although the real-life usage of the phrase long ago lost its exclusivity to London, it retains some of its original associations.

The Oval or Kennington Oval

A cricket ground in kennington that takes its name from a street layout devised in 1790, although the plan was never fully realized. It has a spectator capacity of over 23,000. In 1844 the Montpelier Cricket Club leased 10 acres (4 hectares) of the Oval’s market gardens after it had been ejected from its ground at Walworth. Cabbage patches were buried under turf brought from Tooting Common and an embankment was raised using soil excavated during the enclosure of the River Effra at Vauxhall Creek. Shortly after the ground opened a group of aficionados founded Surrey County Cricket Club at a meeting in the neighbouring Horns Tavern; Surrey played its first county cricket match against Kent in 1846. The first test match in England was staged here, in 1880 (between England and Australia – England won by five wickets). It was after Australia’s victory at the Oval in 1882 that the ashes came into being. In the past the Oval has been associated with various other activities, sporting and otherwise. Most FA Cup finals between 1872 and 1892 were played here, as were England’s first rugby union matches against Scotland and Wales. During the Second World War it was a prisoner-of-war camp and in 1971 it hosted its first pop concert but nowadays the playing area is reserved largely for cricket. At 558 feet (170m) by 492 feet (150m) it has the largest area of any cricket ground and the gasholders on its north-eastern side have become an Oval icon. It is presently known as the Kia Oval, owing to its sponsorship by a car manufacturer. The Oval has given its name to cricket grounds in several former British colonies, including Sri Lanka and Barbados.

Pray, Sir, have you ever seen Brentford?

Dr Johnson’s response to Adam Smith after the Scottish economist had extolled the charms of Glasgow at some length, recorded in James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (1791).

quadriga

A contraction of quadrijugae (Latin quadri-, ‘four’, and jugum, ‘yoke’). In classical antiquity, a two-wheeled chariot drawn by four horses harnessed abreast. The Wellington Arch at Hyde Park Corner is surmounted by a fine bronze group, Peace Descending on the Quadriga of War, executed by Adrian Jones in 1912. The cost of the sculpture was met by Herbert Stern, 1st Baron Michelham (1851–1919), whose 11-year-old son Herman served as a model for the boy who pulls at the reins of the four horses harnessed to the quadriga as a huge figure of Peace descends upon them from heaven.

so long as the stone of Brutus is safe, so long shall London flourish

An old saying referring to the supposed Trojan origin of London Stone and its mythical significance to the city.

(London Stone is a block of oolitic limestone with an uncertain history. The present stone is merely a chunk (perhaps the uppermost part) of the original, which was described as a ‘pillar’, set deep into the ground. There is no record of how or when it came to be fragmented or what happened to the rest of it, but the diminution must have happened several centuries ago; a woodcut of c.1700 shows a stone of the same size as it is today. London Stone has been the subject of various legends, including that Brutus brought it here, that it marked the site of Druidic sacrifices, and that London’s prosperity depended on its safekeeping. The antiquary William Camden thought it to be the point from which the Romans measured distances; another theory is that it was an Anglo-Saxon ceremonial stone or a focus for judicial proceedings. Edward III made it the axis of the city’s trade in 1328, when he granted Londoners the right to hold markets within a 7‑mile (11-km) radius of London Stone, as it had by then come to be known.)

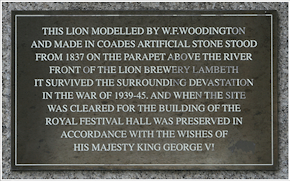

South Bank lion

A 13-ton Coade stone lion that from 1837 stood on a parapet of the Lion Brewery on the South Bank. It is the work of the sculptor W.F. Woodington (1806–93). The brewery was demolished in 1949 to make way for the construction of the Royal Festival Hall but the lion was saved, reportedly at the request of George VI, painted gloss red and mounted on a plinth outside the Waterloo Station gate to the Festival of Britain site. When the station was enlarged in 1966 the lion was relocated to its present prominent position near the eastern end of Westminster Bridge, and stripped to the bare stone.

The Stoop

The informal name of the Twickenham Stoop, formerly the Stoop Memorial Ground, which is situated on Langhorn Drive in north-west Twickenham. The Harlequin (rugby union) Football Club acquired the pitch for training purposes in 1963, subsequently playing its home matches here. Since 2005 Harlequins’ sister rugby league club has shared the ground, which is named after Adrian Dura Stoop (1883–1957), a London-born rugby union player of Dutch descent. Stoop played 182 times for Harlequins, serving as team captain for eight years and later becoming the club’s honorary secretary and then president. Quite separately, ‘the stoop’ was formerly a slang term for the pillory.

Streets of London

Possibly the most famous song about London since the music hall era. Written in 1969 by Ralph McTell (b.1944), who grew up in Croydon, it became a hit for him in 1974 and subsequently served as the title for his 1980s television series and his ‘greatest hits’ album. The song recommends sympathetic observation of the lifestyles of London’s down-and-outs as an antidote to feelings of loneliness or dissatisfaction. According to McTell’s official website there are 212 known recorded versions of the song.

Temple Bar

A location at the point where Fleet Street becomes the Strand, marking the western limit of the City of London. A barrier is first recorded here in the late 13th century (barram Novi Templi). This seems to have been nothing more than a chain between two posts, but by the middle of the 14th century there was an arched gateway here, with a prison on top. This survived the Great Fire of london, but was nevertheless demolished, and a new one was erected in the 1670s to a design by Christopher Wren. In the late 17th century it became the practice to display the heads of traitors impaled on spikes on top of the gate (it was quite a high gate, and those who wanted to get a better view could hire a telescope for a halfpenny). The last shrivelled head apparently fell off c.1772. By the middle of the 19th century Temple Bar’s central arch was becoming too much of an impediment to traffic, and in 1878 it was removed. It was later re-erected in Theobalds Park, Hertfordshire, where it remained for more than a hundred years. In 2004 it was returned to the City, incorporated into the Paternoster Square redevelopment. While the arch itself has gone, its location retains its symbolic significance: a sovereign who wishes to enter the City via Fleet Street, typically on his or her processional way to St Paul’s Cathedral, must stop here and ask permission of the lord mayor of London. The line is marked by a memorial in the centre of the road, erected in 1880, and surmounted by a dragon that is frequently misidentified as a griffin.

Tom o’ Bedlam

An anonymously written ballad telling the first-person story of an Abraham Man, probably dating from the beginning of the 17th century. The work exists in several forms; the ‘mad song’ entitled ‘Old Tom of Bedlam’, reproduced in Percy’s Reliques, bears only a passing resemblance to versions that are nowadays better known. Although it provides some biographical glimpses, much of the ballad consists of ‘strokes of sublime imagination’, as Isaac D’Israeli put it, ‘mixed with familiar comic humour’.

Tottenham shall turn French

Most lexicographers assert that this was an ironic old saying of the ‘pigs might fly’ variety, referring to something that would never happen. However, Francis Grose, in his Provincial Glossary (1787), renders the proverb as ‘Tottenham is turned French’, and explains it thus:

After the beginning of the reign of Henry VIII a vast number of French mechanics came over to England, filling not only the outskirts of the town, but also the neighbouring villages … This proverb is used in ridicule of persons affecting foreign fashions and manners, in preference to those of their own country.

we never closed

The boast of Vivian van Damm (c.1889–1960), manager of the Windmill Theatre during the Second World War. Even when a bomb landed next door, killing an electrician and injuring one of the performers, the show went ahead. Among the theatre’s morale-boosting specialities were groups of unclothed women arranged in ‘artistic’ tableaux, with strict instructions not to move as much as an eyelid. When the doors opened for each performance there was a stampede of men to the front six rows, where the seats had constantly to be repaired.

Westminster Abbey or victory!

The reported words of Commodore Horatio Nelson (1758–1805) before the Battle of Cape St Vincent (1798), at which he was victorious. A year later, as rear-admiral commanding the British fleet at the Battle of the Nile, he is supposed to have said: ‘Before this time tomorrow I shall have gained a peerage, or Westminster Abbey.’ He was afterward made Baron Nelson of the Nile. Vice-Admiral the Viscount Nelson died at the Battle of Trafalgar and was buried with unprecedented pomp in St Paul’s Cathedral in January 1806.

White Horse Final

In footballing history, a nickname for the FA Cup Final of 28 April 1923 between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United at Wembley. Thousands of fans spilled on to the pitch before the start of the game, and it required mounted police, and in particular Constable George Scorey on his 13-year-old white horse, Billy, to clear it before the match could begin. Although Scorey was only one of several mounted policemen on duty that day, his conspicuous white horse gave the name by which the final has always been referred to since. Bolton won the match 2–0.

Yid or Yiddo

In most contexts this is a derogatory term for a Jew. However, to many supporters of Tottenham Hotspur FC it is a badge of honour. It derives from the club’s traditional popularity among north London’s Jewish community. Although originally used disparagingly by some supporters of opposing teams, the term was taken up from the 1960s or 70s by home fans, who nowadays – whether Jewish or not – often refer to themselves as the ‘Yid army’. The club has voiced concern about the phenomenon but, as one Jewish supporter has argued on a fans’ message board: ‘The more the word “Yid” is used in the context of the mighty Spurs then the less power it has as an insult.’

you must go into the country to hear what news at London

This 17th-century proverb was not intended to cast particular aspersions on Londoners’ awareness of events in their own city, but rather to suggest that one may often apprehend the most accurate news of home when one goes abroad.